Table of Contents

It was the year 1962 when a young priest named José Rivas Riera arrived in Cala de San Vicente. The road from San Juan was not yet finished with tarmac – that would not happen until 1963. In those days, one reached the Cala on dusty cart tracks barely wide enough for a horse and wagon. People living near the coast travelled via San Carlos, those from the interior via San Juan. Many walked the six kilometres on foot.

In this remote cove, tourism was just beginning to take its first tentative steps. Two hotels and Punta Grossa were being built – Belgian and Swedish investors had recognised the extraordinary beauty of this place. Yet they all faced one critical problem: there was no electricity.

The young priest was not merely a man of the cloth, but someone who could get things done and knew how to make things happen. The town hall of San Juan entrusted him with a mission that would take years: he was to travel to Mallorca and negotiate to bring electricity to the Cala.

For two years this struggle continued. Journey after journey, discussions, sometimes arguments. Yet the priest did not give up. Finally, an agreement was reached: Punta Grossa and the hotels paid their share, and because it was an official project of the town hall, there was a discount of 20 per cent.

With the money left over that the electricity company GESA did not need, transformers were then built for the entire village. Thus the light came not only to the hotels, but also to the people of Cala de San Vicente – a triumph of community over isolation.

Life in Isolation

Ibiza's long isolation had preserved customs that had long since vanished elsewhere. One of the clearest examples was the traditional division of family property. The principal heir – typically the eldest son – received half the estate outright, and also a proportional share of the remaining half alongside siblings. When holdings were small, the heir often compensated brothers and sisters in cash; when the property was larger, the land itself was parcelled out. This approach kept a viable core for farming with the heir whilst still recognising the rights of other children to a portion of the family wealth.

Land quality shaped outcomes in ways that appear ironic today. The heir usually took the best agricultural plots – deep soils away from salt spray – because that is where subsistence and income were made. Siblings often received rocky, coastal pieces that were poor for cultivation and, for generations, considered of little practical use. With the arrival of outsiders who prized sea views and beach access, those once "worthless" strips became sought after and, in some cases, more valuable than the original farm.

For the locals, the shoreline was seen as a working harbour rather than a leisure space. People called it "Esport", and travelling by boat to Ibiza Town was often easier than going overland. The sea inspired respect and caution: many fishermen could not swim, and storms made coastal living as risky as it was beautiful.

Life Before Tourism

Before tourism arrived, Ibiza lived from agriculture and the sea. The main source of income was the cultivation of almonds and carob beans – these were the products that were exported and with which money was earned. Almonds commanded a particularly high price, and ships came to collect them.

People were largely self-sufficient. Each family produced what it needed: wine, olive oil, even tobacco. The famous "Tabaco Pota" – a special Ibizan tobacco that allegedly smelt terrible but tasted excellent. It was produced in large rolls, about 50 centimetres long and 20 centimetres thick, and each day one would cut off with a knife what was needed. Students from Ibiza are said to have emptied entire bars in Madrid when they lit their homemade cigarettes – all the guests fled from the intense smell.

Sheep and goats were another important source of income. The lambs were sold to Ibiza Town, where there was no livestock farming. The milk was processed into cheese – an excellent Ibizan cheese that, together with fresh figs, bread and olive oil, formed a typical meal. Every family kept pigs for their own consumption. Figs were dried and lasted throughout the winter.

People bought only the essentials: shoes – for they made their own espartograss sandals themselves, their soles reinforced with tar –, shirts and trousers. The women sewed their own clothing, even the traditional mantones. It was a self-sufficient society in which everyone knew how to survive.

Before electricity, people illuminated their homes with quinqués or simple oil lamps – often with already-used cooking oil into which a wick was dipped. Recycling was not a modern invention but simple necessity. For walking through the darkness they used "es fasté" – strips of juniper tree bark that were lit. They did not flame but glowed, and when swung provided enough light for the journey home.

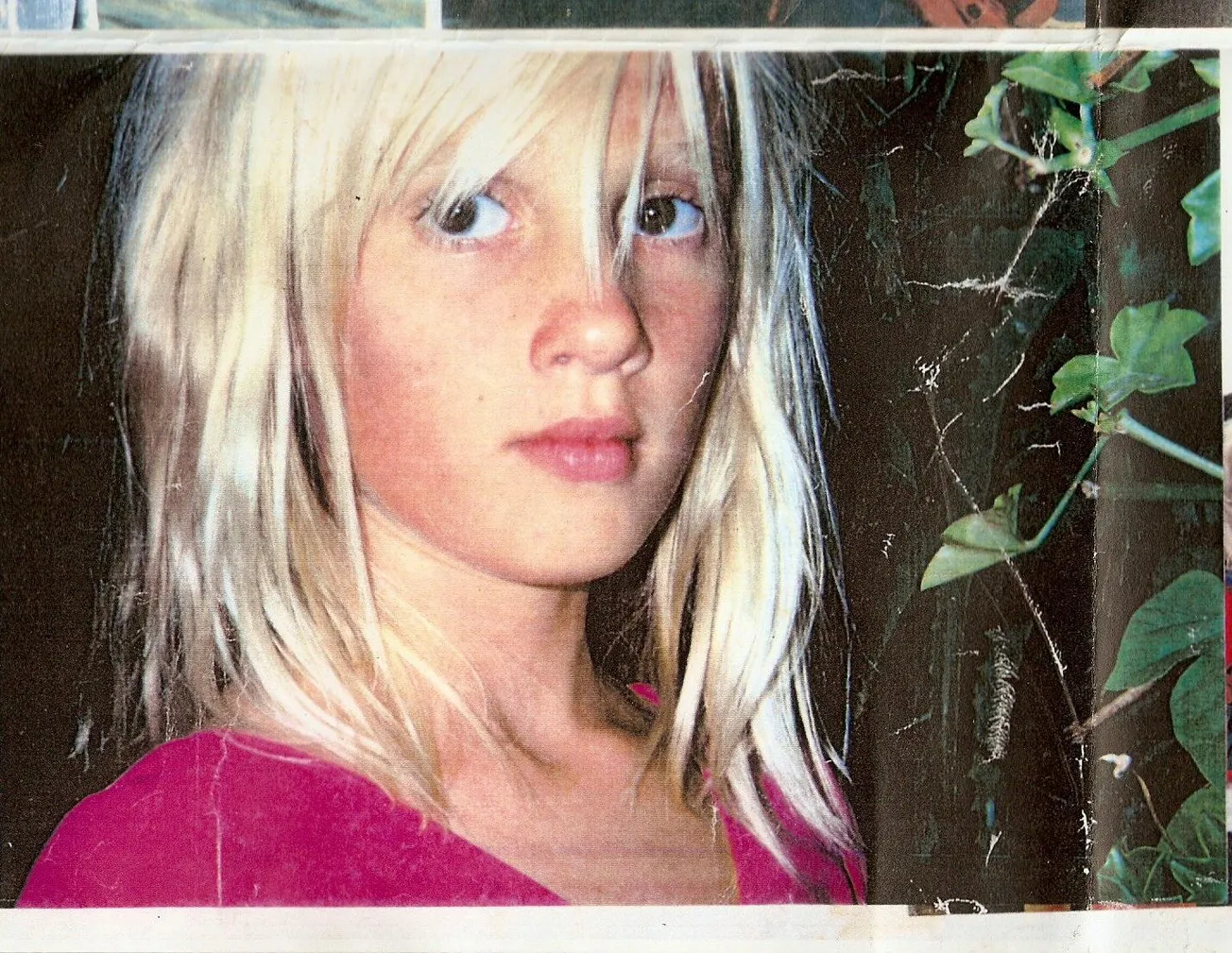

Don Pepe – The Priest with White Hair

Religious life mirrored the island's pragmatism. The priest, affectionately known as "Don Pepe" or in the local variant "Moseña", appears in memory as a diligent scholar and complicated figure in diocesan politics. After studies with Jesuits and aspirations to continue in Rome, he was called back to serve Ibiza and, for a time, stationed in one of the most remote coves.

Early misunderstandings with a bishop gave way to mutual respect, and he became known for his competence and integrity. When a theologian who covered multiple parishes left for a university post, the community asked Don Pepe to return as parish priest, and he did.

Bonds ran deep: he presided at funerals of lifelong friends, visited homes, and even joked with children who would gleefully pluck his white hairs for coins. His arrival in the Cala in 1962 marked not only the beginning of his priestly work there, but also the beginning of a lifelong friendship with the village.

The Teacher and the School

In 1972, Valentín Prats Rincón came to Cala de San Vicente as a teacher – against his will. He had received a scholarship for France, and whilst he spent two months there, he was transferred to Ibiza in his absence. Many of his colleagues had preferred Formentera. When he arrived on a Friday and drove down the road from San Juan for the first time, he thought: "I like this. This landscape is beautiful."

He came to the café – the social heart of the village – and asked for the priest. The children led him to the church and to the school above it. Don Pepe's greeting was characteristically direct: no protocol, no "This is your home". Simply: "What do you need?"

From that moment on, the two were inseparable – the priest and the teacher, the two intellectuals in a village of farmers and fishermen.

The school itself was a remarkable story. Until then, teaching had taken place in private houses. A Valencian teacher had told the parents: "If you want teachers to come and stay, you must build a school with accommodation." The community of the Cala, though so remote, had a special character – the children of the lighthouse keeper, the priest, and from San Juan all went to school; families were very concerned about education.

So they set to work. The entire village contributed: some paid money, others transported materials with their carts, still others provided beams. They founded an association called "El Progreso" which remains the owner of the building to this day. The school was built half as accommodation, half as classroom – only for boys, as girls were still taught separately in private houses at that time.

Valentín was the last teacher in this school. From 1976 to 1977, all children then went to San Juan. Today the building is a "Campo de Aprendizaje" – a learning camp where children discover nature. It is run by Eva, Valentín's daughter, who also became a teacher.

The Café – The Village's Second Heart

Besides the church and the school, the café was the only public place. Pepe del Café and his family ran not only the village pub but also a small shop, tobacco sales, and the post office. It was the place where everyone met, where cards were played, where news was exchanged.

In the 1990s, writers, artists, and politicians passed through – often unrecognised or simply left in peace. A Dutch artist with a wide-brimmed hat set up a typewriter in the courtyard. A German politician dropped by incognito for coffee. Fame mattered less than neighbourliness; visitors were treated as people first.

Today a great-grandson of the founder runs the establishment – he married a Thai woman and turned it into a Thai restaurant. But inside, everything has remained as it was before, a living monument to the village's history.

The family has even contemplated writing a history of the café – a fitting project for a place where everyday conversations kept the island's intertwined stories of land, faith, and work alive.

The Special Community

Cala de San Vicente was, due to its isolation, a village with special cohesion. When, after the Spanish Civil War, which also left its mark here, peace returned, the community consciously chose reconciliation. Like an irrational thought, as Valentín recalls: "We must carry on living, and we must live in peace." And so it was. When he arrived in 1972, he would never have guessed what had happened without being told the stories. Everyone went to Mass, everyone watched football together, everyone took part in processions.

This unity also showed itself practically: when someone said "We should do this", they did it together. The St Anthony's feast in January was celebrated with a paella, formerly on the beach, later at the club.

The isolation also had an unexpected consequence: in the past, there were often nine children in each family. The land was only enough for one heir; the others had to emigrate. Today the population is smaller, but people stay, for there are restaurants, shops, work. One no longer needs to leave.

A Village in Transition

When José Rivas Riera arrived in 1962, there was no tarmac anywhere in San Antonio, Santa Eulalia, San Juan, or San Miguel. He was 25 years old then. Today he is 87 and has witnessed the complete transformation – from cart tracks to tarmacked roads, from oil lamps to electric light, from self-sufficient village to tourist resort.

Yet despite all the change, something has remained: the special spirit of the Cala, where people stick together, where a priest asks "What do you need?" instead of exchanging pleasantries, where a café remains the heart of the village across generations.

Both men, José and Valentín, were born in 1937. They have been inseparable friends for over 50 years, the chroniclers of an era in which Ibiza transformed from the ground up – but never lost its core.

This story is based on an interview with José Rivas Riera (priest) and Valentín Prats Rincón (teacher), both born 1937, recorded in Cala de San Vicente, November 2025.