Table of Contents

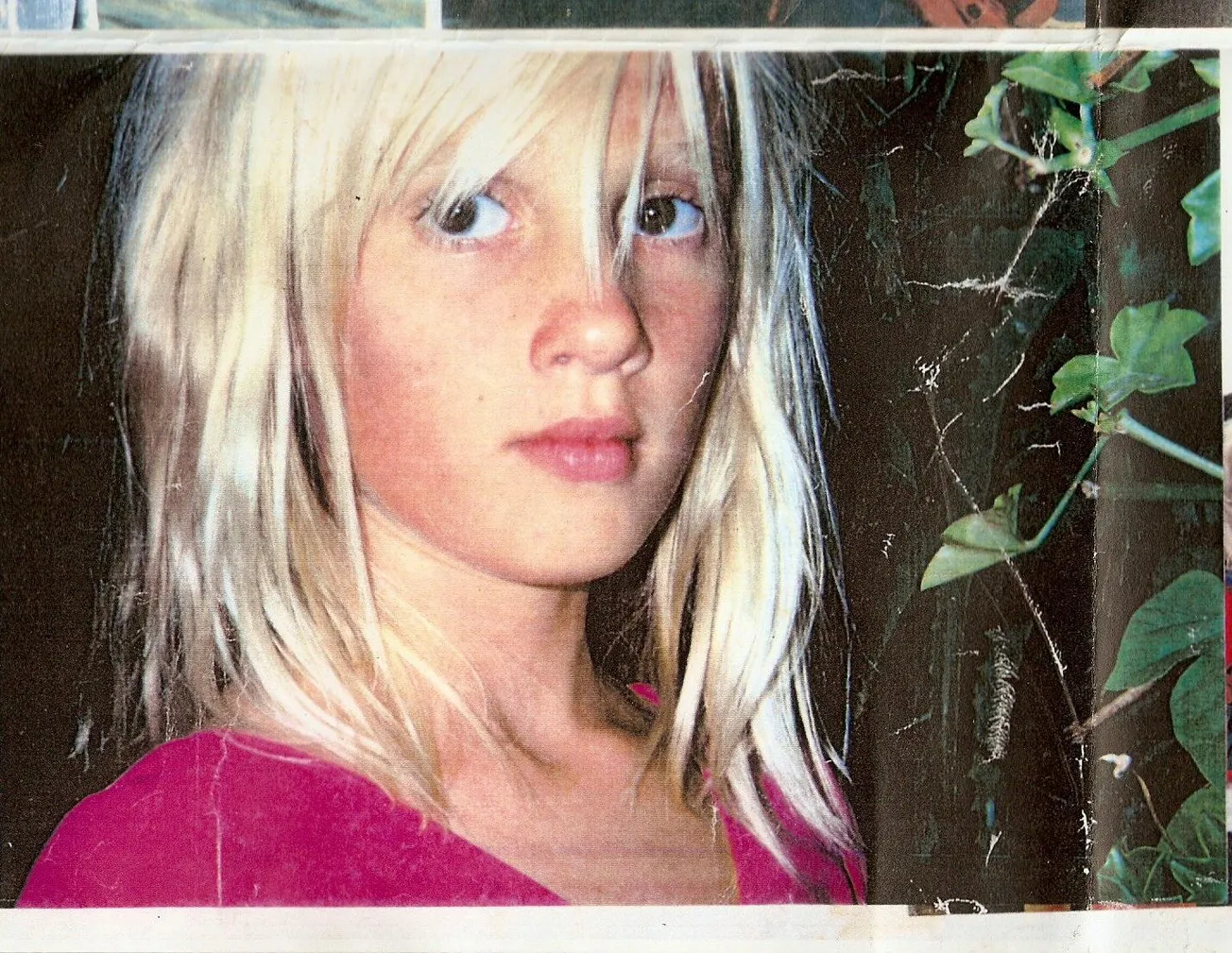

I was born in 1984 in Sant Carles on Ibiza, the daughter of German parents who had come to the island in the late seventies. My brother and I grew up here until we moved back to Germany when I was ten. But Ibiza never truly let me go. Every summer I returned – mostly not just for holidays, but to work as well. This was where my chosen family was, as I call them. People who weren't connected by blood, but by this island and everything we'd experienced together.

The Contrast of the Seasons

What's stayed with me most strongly is the extreme contrast between summer and winter. In summer, everything was warm and beautiful and sunny and cheerful – lots of people, lots of wonderful experiences. But winter was like a different island. Empty. Damp. Cold. The houses had no proper insulation, everything was clammy. Emotionally, this time felt like a grey fog hanging over everything.

When I walked through the old town of Dalt Vila, I saw the colourful, painted wooden shutters everywhere, closed in front of the shops below the fortress walls by the harbour. The streets were deserted. It was a completely different world from the vibrant summer.

Life in the Fincas

Back then we lived in fincas without running water, without electricity, sometimes without proper toilets or showers. The first telephone I remember was in Bar Anita – that was essentially our real social media of the time. That's where you met up, where you collected your post. Every few months we'd drive to the phone box and ring our grandmother. That was an event.

The hippie parents – including my own parents, to be honest – weren't particularly good at creating a cosy domestic atmosphere where a child could really feel comfortable. The party lifestyle that somehow still worked in summer under the Mediterranean sun had a completely different quality during the dark winter months.

The Big Family

But despite everything – or perhaps precisely because of it – Ibiza truly was one big family back then. I remember a story a hippie woman told me years later. At a party at Las Dalias, she'd pushed me as a baby in a basket under a pool table and then forgot about me for a while. Sounds terrible, I know. But there was always someone looking out. Always. That was what was special about this community.

I still remember how at parties someone would often turn up in their VW bus with a huge mattress in the back. When we children got tired, we'd simply climb in and sleep whilst the adults carried on partying. After the party, the parents would come and collect their children – sometimes they'd accidentally take the wrong ones, sometimes they'd forget some completely. But somehow it was always okay. There was no real danger. Everyone knew each other, looked out for one another. That was just understood.

The Peluts and the Ibizenkos

The locals called the hippies peluts – a Catalan word meaning "the hairy ones", referring to their long hair. It wasn't an insult, but rather an affectionate, colloquial description of these long-maned folk who had suddenly appeared on the island.

What still amazes me today is the extraordinary tolerance of the Ibizenkos. Imagine this: a strictly Catholic society, women in black dresses with headscarves, and then these peluts arrive, live in their houses, throw parties, run around naked on the beach. The hippies could basically do what they wanted here, and the Ibizenkos let them get on with it. There was this openness from both sides, and it was actually quite peaceful.

The landlord relationships showed this pragmatic openness very well. You'd rent the house to the hippies but keep one or two rooms for yourself. That way the Ibizenkos could continue to work their fincas, tend their fields. It gave both sides clarity and also gave the locals a degree of control.

Many of these old houses stood empty back then – because of complicated inheritance matters, often no one looked after them. Through the hippies, they were brought back to life. In a way, a piece of architectural cultural heritage was preserved, something hardly anyone thinks about today.

The Ibizenkos continued living their culture – their traditions, their religion, their festivals. But they were involved and integrated in what was happening on the island. As long as the peluts respected everything, it worked well. And mostly they did.

Over time, in the seventies and eighties, both worlds began to blend. The younger generation of Ibizenkos started trying things that didn't belong to their traditional culture. Then suddenly there was an Ibizenkan dealer, because someone realised you could make good money from it. Everything mixed together a bit, naturally it took time, but it happened.

A Latchkey Child in Dalt Vila

When we later lived in Dalt Vila, I was a typical latchkey child. I had a chain round my neck with my house key hanging from it. I could come and go as I pleased – at least theoretically. There was rarely anyone at home. My father was away, my mother was out a lot, working, often dropping me off with other mothers, friends, whoever happened to be around and could look after me.

Eveline, whom I still call my foster mother or second mother to this day, was there for me mainly in summer. In winter she was usually away, then I stayed with other people. That's why my connection to other children became so important. I didn't have that solid connection to family members, so I found it in classmates and friends.

My childhood friend Esther is almost like a sister to me. Her mother was completely different from mine – she often had me round, and we played together a lot. We sort of grew together, and we still know each other today. There's definitely a special bond there.

Otherwise I spent a lot of my time with my gypsy friends and their families. I simply sought out places where someone was. Where I might get something to eat. Where I felt safe.

School and Creative Survival

School was also a place where I had to learn to organise my basics myself. I went to a girls' convent school, and during breaks I developed quite an entrepreneurial spirit early on. I'd plait complicated braids for the other girls – all sorts of artistic hairstyles. For that I'd get 25 pesetas, those coins with the hole in the middle.

I'd take a shoelace from my shoe and thread the pesetas onto it like beads. That's how I made my own peseta necklace. With the money I'd earned, I'd buy myself something to eat after school, or if the girls didn't have any money, they'd simply give me part of their packed lunch.

My favourites were chorizo bocadillos and strawberry-cream Chupa Chups. When I eat that today, it instantly transports me back to that time. Eight years old, inventive, hungry.

Summer in Dalt Vila

In summer there were other ways to earn a bit of money. With my gypsy friends, I'd stand at Portal Nou – that tunnel through the old city wall. Back then there was no lighting, and when you went in, you couldn't see the end. Most tourists didn't dare go through.

We'd stand at the entrance and charge admission, leading people through. Sometimes we'd even do proper guided tours and naturally make up the stories. Because I'd grown up multilingual, I could translate what my gypsy friends invented – into German, English or French. The tourists always found it very amusing and gave us pocket money for it. It was fun.

Afterwards we liked to sit on the old walls and eat pipas – those sunflower seeds in their shells. You crack them with your teeth, eat the kernel and spit out the shell. A bit of a mess really, but we loved it. We'd watch the tourists walking through the alleyways, tell each other stories and simply enjoy the summer.

The Dark Side

But of course there was also the other side of this childhood. The side you don't like to talk about, but which belongs to it if you want to be honest.

For children, it was difficult to experience how adults – often your own parents or their friends – were changed by substances. Even if they perhaps felt good, as a child you noticed that something was different and abnormal. A distance emerged with that person. And when those are your parents, you don't really feel at home. There's no proper communication possible. It's a disruptive factor, and as a child it simply doesn't feel nice.

In winter in Dalt Vila, I had to learn which alleyways I'd better avoid. There were children who sniffed glue, completely out of it, and sometimes tormented cats or aimed slingshots at pigeons. The gypsies were my friends, but there were aspects to that life that really frightened me. It was a constant thrill, that ambivalence.

Different Paths

The children of our generation developed very differently. Some were pulled into it – you often unconsciously repeat what you've been shown, whether you want to or not. Then you have to live with the consequences.

But most of those who made it tended to go in the opposite direction. Many left the island, only come to visit now, because that lifestyle simply isn't for them. Others live a bit isolated up in the hills and have turned to meaningful projects – helping animals or people, finding other purposes.

Rewriting One's Own Story

For a long time it was difficult for me to talk about my childhood on Ibiza. When I left at ten, I couldn't imagine ever building my life here. It felt very limited. For someone at that age between ten and twenty, who wants to develop and discover new things, such a small island is simply restrictive.

I studied drama on the mainland – I couldn't have made a career of it on Ibiza. On the one hand, I always felt somewhat at home here, on the other hand there was this constant search for another home. I had to process these childhood experiences first, come to terms with them.

There was a lot of pain through all the crazy things that happened in that whole party world. But over time, I was able to rewrite my past and also my present. That pain I associated with my childhood on Ibiza for a while is gone.

Today I can recognise that it was precisely that pain that made me the person I am. Perhaps it made me sensitive to wonderful and brilliant things. From the negative experiences that I perceived as negative back then, I learned things that enable me to be a positive person today.

It might not be the same for everyone, but that was my experience. And for that I'm ultimately grateful.

Recorded by Andreas for Ibiza Insights, December 2025